Despite having just 4,600 employees, the Securities & Exchange Commission plays an outsized role as the primary regulator for $115T of securities traded in the US every year.

Hey friends -

With last week's letter celebrating the first year of Fintech & Finance, we missed another important birthday. The Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) turned 88!

Before the SEC, the US had little to no oversight of securities markets. Its origin and subsequent evolution are key to why the US has the most competitive financial markets in the world.

In this week's letter:

The SEC: Piggly Wiggly and other stock market shenanigans in the '20s, what the SEC actually does, and how it's structured to do it

Thoughts on business cycles, why we're experiencing many once-in-a-lifetime events all at once, and more cocktail talk

Rum & Friends, an easy-to-make, highly versatile cocktail

Total read time: 16 minutes, 23 seconds.

Let's take a trip down memory lane to the years leading up to 1934. I think we're all familiar with Black Tuesday and the stock market crash of 1929, but there was so much more going on.

A place to start is that the real damage from the 1929 crash played out over three years. Yes - the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell almost 50% from 381 to 198 between September and December 1929. But it didn't bottom until it hit 41 in late 1932, a full 89% later.

The journey to the bottom wasn't smooth sailing. It was interrupted no less than six times by bear market rallies.

It was a veritable rollercoaster of a market for the ten percent of the population invested in the market. It's probably a good thing more people weren't involved. The market was hardly fair for the little guy.

Two stories to give you a sense of markets before the SEC. The first is about a groundbreaking grocery store called Piggly Wiggly.

Piggly Wiggly was truly a revolution in grocery. No longer would a shopkeeper pick items for you, instead you could wander the aisles and pick groceries yourself. It was the first self-service grocery store. It revolutionized grocery shopping.

Without the overhead of paying clerks, Piggly Wiggly could both handle more customers and beat competitors on price. It led to an explosion of stores, over 2,500 at its peak. The new way of shopping drove the company to many other firsts - the first checkout counters, the first shopping carts, and the first turnstiles. In many ways, it was the sexy tech company of its time.

In 1922, after multiple years of rapid expansion, some of the New York franchises ran into financial trouble. Investors took the bad news as an opportunity to start a bear raid on the company - borrowing stock and selling it short to depress the share price. Founder Clarence Saunders didn't take kindly to their actions.

Short selling works by borrowing and then selling shares with the goal of eventually buying back the shares at a lower price. Borrow the shares, sell the shares for $100, wait, buy back the shares for $25, return them to the owner, and keep the $75.

The way to get back at short sellers is by buying up the available supply of shares, driving the price up above where they shorted it, and calling in the loans. In essence - corner the market. It's what happened with Gamestop not too long ago. It's what Sanders attempted to do with his Piggly Wiggly.

Sanders borrowed $10 million from banks and bought an astonishing 98% of the outstanding shares. The share price skyrocketed from $39 to $124, a disaster for the short sellers.

But in a market that tolerates shenanigans, no trick is too dirty. The short sellers convinced the stock exchange governors to suspend trading in Piggly Wiggly and grant them an extension before they needed to pay up. The share price subsequently collapsed, the short sellers were able to scrounge up what few shares remained available for purchase, and Sanders lost $9 million. Unable to pay, he declared bankruptcy.

Cliff Mining President, Rodolphe Agassiz, probably didn't have much to do day to day. Its heyday as a leading copper producer was long past. So you can imagine Agassiz's excitement in 1926 when a geologist informed him the company may be sitting on a huge lode. [footnote] [a vein of metal ore in the earth]

Agassiz went ahead and did what any respectable insider might do at that time - he went out into the market and purchased a bunch of shares in his company ahead of the information becoming public.

Shareholder Homer Goodwin subsequently sued him. He claimed he would not have sold had the geologist report been disclosed. Amusingly, the geologist's report was ultimately wrong and the share price fell back to earth, but that's neither here nor there. The issue at hand was insider trading.

The case made its way to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. In 1933, it issued its ruling:

>Fiduciary obligations of directors ought not to be made so onerous that men of experience and ability will be deterred from accepting such office. Law in its sanctions is not coextensive with morality. It cannot undertake to put all parties to every contract on an equality as to knowledge, experience, skill, and shrewdness.

Agassiz was exonerated. There was no question of whether he "had certain knowledge, material to the value of the stock, which the plaintiff did not have." It was simply considerable acceptable to trade on it.

Such shenanigans, while great for storytelling, undermine public confidence in the stock market. If everyday people think the market is rigged, they won't participate. The few that do are often exactly the ones you'd like to keep out.

The Senate Banking Committee started hearings in 1932 to investigate what had happened and what could be done. Out of those hearings came the bedrock of securities regulation in the US.

Securities Act of 1933 ('33 Act) - required that the offer and sale of securities be registered. Registration was originally with the FTC until the SEC was formed under the '34 Act. Registration essentially means disclosure. When companies intend to sell securities, they must produce audited information about the state of affairs and financials for which they are liable if misrepresented.

Glass-Steagall Act - separated commercial and investment banking. Also created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

Securities Exchange Act of 1934 ('34 Act) - regulated secondary market activities and the actors that participate. It create the SEC, a new regulator, to enforce both the provisions of the '33 Act and the '34 Act and granted it the power to pursue civil cases against both individuals and companies that violate securities law.

The SEC was born and it had teeth. With Joseph P. Kennedy, father of President John F. Kennedy, as its first chairman, it also had a leader deeply familiar with every dirty trick on Wall Street. After all, he had made millions as one of its foremost insiders.

There are two ways to understand the SEC - what it does and how it's structured. The former follows from the '34 and informs the latter. While securities markets have changed, the mission has remained virtually unchanged almost 100 years after the organization's founding.

Understanding how the SEC operates may seem dry and uninteresting, but the structure has nonetheless proved foundational for the success of our markets. That's not to say it couldn't be done better, but so far we haven't seen anyone do it successfully.

There was substantial talk in the early 2000s that US markets were losing their luster and that our rather messy regulatory environment was to blame. While there is truth to the accusations that the US can do better, our markets faired far better during the Great Financial Crisis than most peers around the world. Capital subsequently came rushing back in what is likely to continue to be an ebb and flow over time.

I say messy because the SEC's jurisdiction is arbitrary. In the US, we have two market regulators - the SEC and the Commodities and Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). That division is a historical anomaly arising out of a disagreement between an entrenched faction in New York who didn't want a bunch of midwestern farmers regulating their securities markets and another in Chicago who didn't want "those Wall Street types" touching their commodities.

What we got was the worst of all worlds - two regulators endlessly stepping on each other's toes. The Great Financial Crisis exposed the gulf between the two when it became apparent that neither was responsible for derivatives, a responsibility that now sits with the CFTC. Cryptocurrency is the latest to suffer from a lack of clarity, but it certainly won't be the last.

Such a set up is unusual. Despite its shortcomings, it seems to work reasonably well.

The SEC has a three-pronged mission to:

Protect investors

Maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets, and

Facilitate capital formation.

Protecting investors starts with the disclosure process. While the '33 Act established requirements for companies to register upon initial offering, the '34 act extended those requirements to the regular ongoing reporting we have today in the form of 10-Ks, 10-Qs, and related statements. Since 1995, those statements have been hosted in EDGAR, the Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval system.

When you take a step back, the scope is extraordinary. In one fell swoop, the US passed a regulation that required companies to disclose their most intimate details and put in place a cop if they didn't.

Basics we now take for granted like accounting standards had to first be invented and then enforced. The SEC initially undertook this particular obligation itself but later outsourced it to the accounting profession. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) determines the rules for Generally Accepted Accounting Principles and the SEC enforces its use in reporting. It's just one of many examples.

Preventing fraud is the second major investor protection. There are two key provisions. Section 10(b) of the '34 Act broadly prohibits attempts to defraud and imposes liability for misstatements or omissions. It was updated in 1942 to detail that fraud could be perpetuated when purchasing securities, not just when selling them. The update eventually provided the basis to prosecute inside trading.

Section 9 prohibits manipulation through false or misleading predictions about price movement or other misinformation about a security, short selling, pegging, fixing, or stabilizing of securities. It also empowers investors to sue.

Together, Section 10(b) and Section 9 effectively outlawed most of the worst abuses of the '20s and created a firm foundation to pursue any future shenanigans that might arise. Both investors and the SEC continue to rely on the sections today, bolstered by decades of case law.

There's still a lot of space between outright fraud and well-functioning markets. It's the focus of the SEC's second prong - fair, orderly, and efficient markets.

It starts with the registration and regulation of its participants including exchanges, brokers, dealers, and investment advisors. Much of the work is delegated to Self Regulatory Organizations like FINRA - the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority.

FINRA is an independent, private organization but nonetheless exercises rulemaking, enforcement, and arbitration over the industry and its participants. It's a big job - there are over 28,000 entities to regulate and the number increases almost every year.

Before electronic trading, the activities of market participants were substantially simpler. The ability to trade and match trades anywhere required materially updated definitions.

Alternative Trading Systems (ATSs) are a prominent current example. They're a subset of exchanges that directly match buyers and sellers without posting offers publicly on a traditional exchange. Most are registered as broker-dealers and are less stringently regulated than formal exchanges.

They first emerged to facilitate large block orders among institutional investors. They're now increasingly used to facilitate trades in unregistered securities among accredited investors. Most investable collectibles - cars, comic books, watches, etc. - are structured as standalone limited liability companies (LLCs) that hold the underlying asset. Investors then trade shares of the company using an ATS.

The work to properly regulated ATSs continues today. Newly proposed rules, if approved, would require any "communication protocol" that connects buyers and sellers to register as an ATS. It attempts to rope in the many firms that have effectively been facilitating every aspect of trading except the actual exchange of assets and payment.

All of these regulations are for naught if not to facilitate capital formation. The core purpose of our securities markets is to connect those with capital to those without.

Capital formation takes two forms - public and private. IPOs and SPACs are among the most high-profile public securities offerings, but debt issuances make up a greater share of the value. Venture capital rounds for startups similarly make headlines for private capital formation, but private equity fundraises and investments into hedge funds are larger. In total, almost $5 trillion was raised in 2020 across public and private markets.

Private markets are by their very definition, private. There are several registration exemptions each with nuanced requirements that must be met. Reg D exempt securities cover most of the venture capital world - it's the exemption through which startups typically raise capital from accredited investors.

If you're an investment fund rather than a startup, you need a different exemption. You might structure your firm as a 3(c)(1) fund where you are exempt from registering if you stay below a 100 accredited investor threshold limit (250 if you're in venture capital). It's one of several exemptions embodied in the Investment Company Act of 1940, yet another regulation that furthered the SEC's reach.

"Private" and "exempt" don't mean hidden or unregulated. It means they're exempt from many of the public registration and reporting requirements that are imposed on publicly listed companies. Private companies still must report a more limited set of information to the SEC. As you might expect, it's a constant tug-of-war as the SEC prefers more disclosures and investors prefer fewer.

It's a big mandate - over $115 trillion in securities are traded in US markets every year. The SEC is nonetheless a relatively small organization with just 4,200 employees. It's been very deliberate in its structure to effectively regulate.

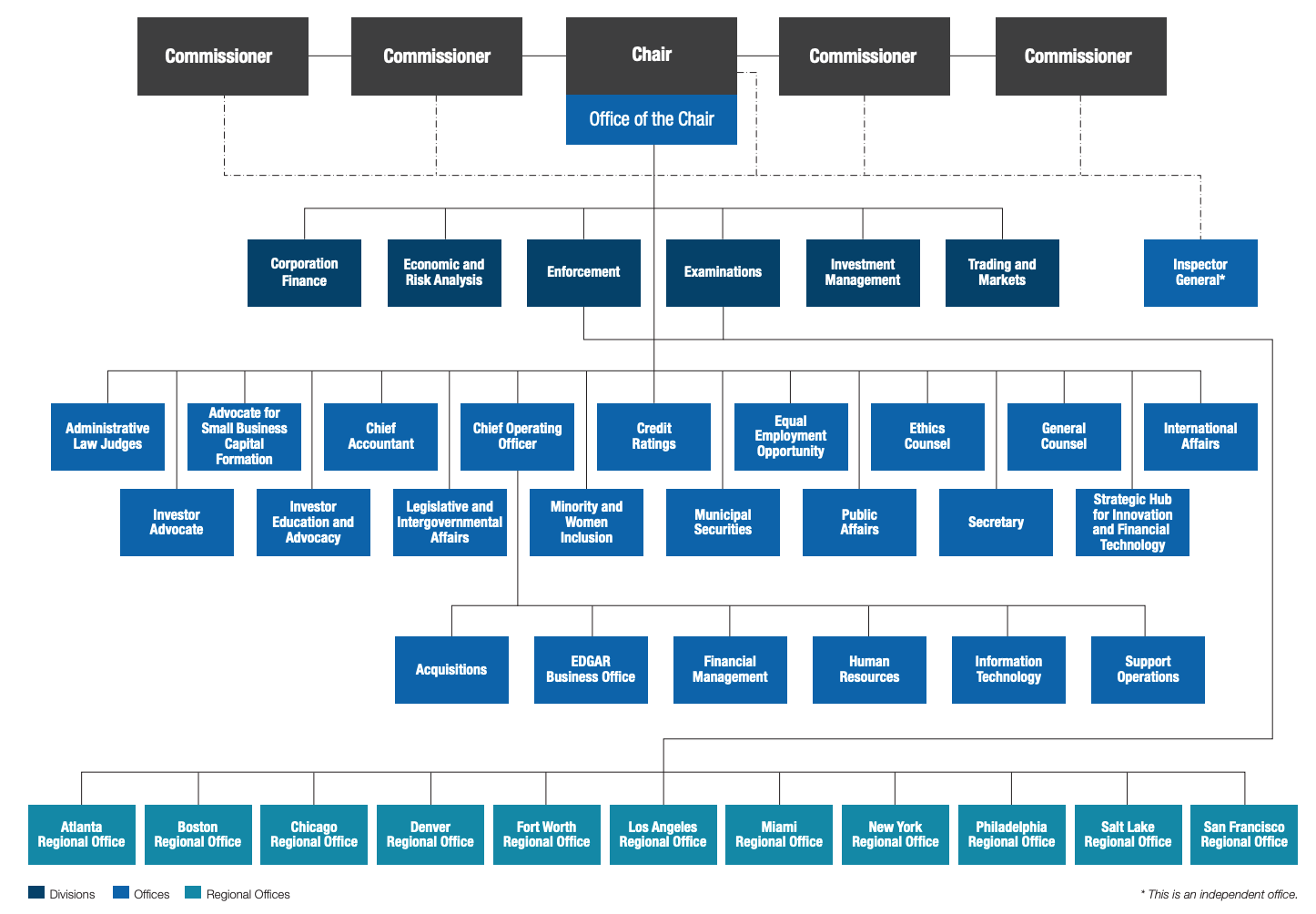

The SEC is structured to be independent and bipartisan to the extent possible.

It's run by five commissioners appointed by the President. No more than three commissioners can be from the same political party and their five-year terms are staggered to minimize the influence of any one President or congress. While the President can appoint commissioners, (s)he cannot fire them.

In a staggering abdication of responsibilities, the SEC's bipartisan structure has caused material problems in recent years. Multiple Presidents, including our current, have failed to appoint the full contingent of commissioners in order to preserve a super-majority of partisan appointees. It's hamstrung an already spread-thin organization.

While there is a chairman - currently Gary Gensler - the commissioners largely operate by simple majority. Many of the decisions made by the SEC don't actually involve the commissioners themselves, rather they are executed by career officials to whom the commissioners have delegated authority.

Below the commissioners sit divisions, offices, and regional offices.

Divisions play the biggest role at the SEC.

Corporate Finance oversees the regulator filings and other disclosures from public companies. It also provides what the SEC describes as "interpretative guidance." That can range from guidance on new accounting standards to No-Action relief that permits new types of activities.

Paxos, for instance, trialed a new securities settlement platform for two years with live equities trades under a No-Action letter. The company doesn't yet have the clearing license it needs to operate a full version of the platform, but it can't get the license from the SEC without demonstrated success. The No-Action relief gave them the cover needed to run the trial.

Trading and Markets is generally responsible for "fair, orderly, and efficient markets." It provides day-to-day oversight of the self regulatory organizations, exchanges, and other market participants. An important and often overlooked mandate is oversight over the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC). SIPC operates similarly to FDIC as a member-funded non-profit that insures investor accounts held with brokers up to $500,000.

Investment Management administers the Investment Company Act of 1940 and Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Most of the funds that retail investors interact with - including mutual funds and ETFs - fall under the Investment Company Act. Most investment advisors fall under the Investment Advisers Act.

The division oversees just about everything to do with funds and advisors, from rulemaking to analytics on the asset management industry. It plays a critical role for retail investors in particular given their exposure to funds and advisors.

Enforcement is the largest of the SEC's six divisions, accounting for 44% of the organization's costs. While important, I find it disappointing that a regulatory agency with an enforcement division seems as if it has become an enforcement agency with a regulatory division.

Enforcement conveniently publishes an annual report with highlights and statistics about its cases. While I wouldn't poke at a regulator, their own published data is so overwhelmingly ridiculous that it begs deeper analysis.

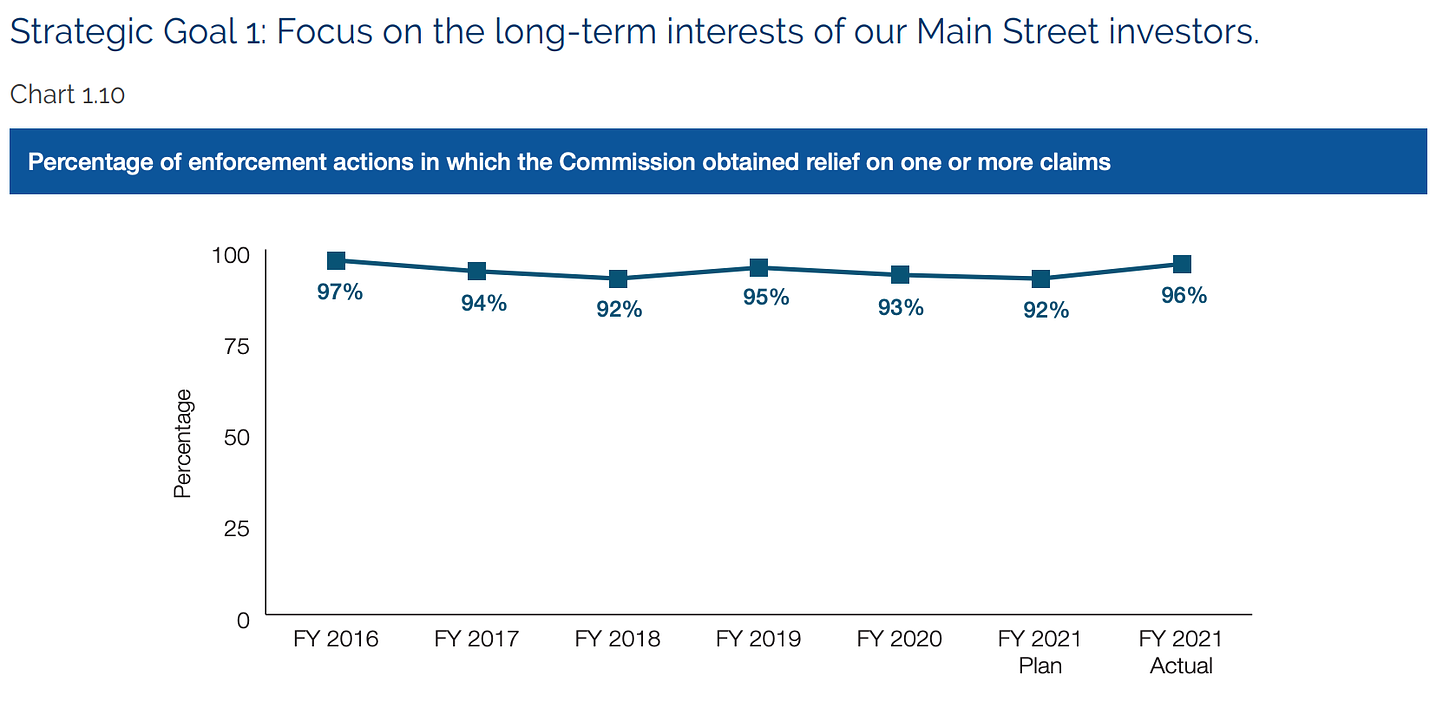

The SEC wins well over 90% of the cases it brings forward, an absurdly high percentage. Firstly, it's strong evidence that the SEC prioritizes easy-to-win cases over those with greater investor impact. That's disappointing. Second, it reflects a biased system.

When the SEC decides to pursue an enforcement action, it can choose to bring suit in federal court where defendants get normal protections and rights. Or it can bring suit in an administrative proceeding before an in-house administrative law judge appointed by the Commission. As of 2015, the SEC had a 70% win rate in federal court but an astonishing 90% rate in-house. It's nice being judge, jury, and executioner.

Times may be changing. A Fifth Circuit ruling in May of this year determined that the SEC's processes violated the defendants' right to a jury and that Congress had unconstitutionally delegated legislative authority to the SEC in the form of allowing the regulator to choose the venue for trials. While that case may yet be appealed, a second case concerning the same constitutionality challenges has already been fast-tracked to the Supreme Court for next year's docket.

Examinations conducts on-site exams and certifications for market participants.

Economic Risk and Analysis is relatively new and emerged from the Great Financial Crisis in an effort to establish a single hub for the enormous volumes of data the SEC collects. Time will tell if it's able to break down data silos across the organization.

The Offices are less important. They make up just 4% of the SEC's spend. That disappointingly includes the Strategic Hub for Innovation and Financial Technology, the SEC's arm to engage the fintech world.

I'm hopeful that the SEC returns to its roots.

Read again the focus of protecting investors - it's about preventing fraud and ensuring that investors have adequate disclosures. There's nothing in there about a discriminatory wealth test that says you have to have a salary over $200,000 or a net worth over $1 million to invest in certain securities. Yet those are the regulations we have today.

There's tremendous opportunity for the SEC to provide clarity on and strong regulations around cryptocurrency, yet it's doubled the size of the crypto enforcement team without any meaningful rulemaking. The agency could move ahead with the now many months delayed comment period for Paxos's clearing agency license, yet its prioritizing incremental improvements in retail investor order execution.

It's a pattern of "we know what's better for you than you do" coupled with prioritizing headlines rather than meaningful change. It's pursuing babysitting, not regulating, and it undermines the core mission of the SEC.

I'm not alone in voicing my frustration. None other than current Commissioner Hester Peirce stated the same:

Sometimes, and now is one of those times, we prioritize investor protection with a very narrow concept of what investor protection is. It's trying to stop investors from making investment decisions that we regulators think are not wise for them to make. Again, it takes away their autonomy over their own lives if we decide what we think they should participate in as investors...

Right now we're in this uncomfortable position of telling investors crypto is too dangerous for you. We don't want you to participate in crypto. That manifests itself in lots of different ways. The irony of that approach is that you actually make it much more difficult to identify the fraudsters from the good actors, because when you don't have a clear rule set in place, it's very hard to distinguish who's on the right side of the line and who's on the wrong side of the line because nobody understands what the line is. I think the way we've gone about this has undermined every prong of our mission.

Yet despite my concerns and objections, we continue to have the most robust securities markets in the world. As long as there are people like Commissioner Peirce continuing to push for SEC to think deeply about how it can facilitate healthy, functioning markets for everyone, I have no doubts we'll continue to lead for another 88 years.

Howard Marks is one of the all-time great investors. His thoughts on risk and cycles are particularly poignant in the current environment. I've been rereading his letters and book (The Most Important Thing), spending extra time on those written in the wake of 2000 and 2008. For those with the stomach, his comments from 2001 ring particularly loudly, "Being positioned to make investments in an uncrowded arena conveys vast advantages. Participating in a field that everyone's throwing money at is a formula for disaster." (Howard Marks Letters)

Chuck Akre is a thoughtful, long-time money manager. He emphasizes two particular philosophies that I've been revisiting. The first is his three-legged stool model for identifying investments: high returns on the owner's capital, quality and integrity of the management, and the record of and continued opportunity for reinvestment. The second is his philosophy on selling: unless something impairs one of the three legs, don't. (Invest Like The Best)

It feels like we're living through many once-in-a-lifetime events all at once. The math isn't intuitive, but there's actually a high probability of many "near impossible" things happening all at once. "If one person plays the lottery, the odds of picking the winning numbers twice are indeed 1 in 17 trillion. But if one hundred million people play the lottery week after week – which is the case in America – the odds that someone will win twice are... 1 in 30." (Collaborative Fund)

We tend to impose how we sense the world on all other organisms around us. We struggle to imagine what the world looks like if we saw ultraviolet like bees, sensed heat like snakes, or smelled CO2 like mosquitos. The article is a wonderful exploration of the wild and weird ways animals have evolved to sense the world around us. (The New Yorker)

A highly versatile, easy-to-make summer cocktail.

2.0oz White Rum

1.0oz Lime Juice

0.5oz Cointreau

0.5oz Ginger Simple Syrup

Seltzer

Pour everything into a Tom Collins glass. Add ice until the liquid comes two-thirds of the way up the glass. Top with seltzer and enjoy! (If you have a bar spoon with a long, twisted handle, you can pour the seltzer down the spoon so it reaches the bottom of the glass. The bubbles will cling to the spoon).

We'll get into proper tiki drinks and more as the summer progresses. This is something I pulled together in less than five minutes as we arrived back home sweaty and tired after a weekend away. Ginger simple syrup - and most syrups - will keep for 3+ months in the freezer in a glass jar. I keep a bunch on hand for occasions just like this. I wanted something summery (bubbles!), but with that balance of acid (lime), spice (ginger), and sweet (Cointreau and simple syrup). If you're looking for something similar on a hot summer day, keep the 4:2:1 booze to acid to sweet ratio and play around. Swap rum for tequila or vodka, lemon for lime, ginger for basil or just simple syrup, and so forth. It's wonderfully versatile and you practically can't go wrong!

Cheers,

Jared